2022

13 black and white photographs

hand printed gelatin silver prints on Ilford Art 300

50 x 50cm

edition of 3 + 2 AP

13 black and white photographs

hand printed gelatin silver prints on Ilford Art 300

50 x 50cm

edition of 3 + 2 AP

Olinda (finalist, 2022 Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize)

Artist Statement

Smother is a contemporary reinterpretation of the life of the much loved Lady Bushranger Jessie Hickman (1890-1936) who adopted many roles and disguises as a young, travelling circus performer and in later life as a bushranger in the Kandos/Rylstone region of NSW. Williams photographed Kandos locals in locations known to have been frequented by Hickman to reveal her elusive identities in a historical context, where women shift like phantoms through the archives with names and roles ever-changing. Much like the mysterious, hand printed final imagery that emerged from the film negatives in a traditional black and white darkroom. The word ‘smother’ is circus jargon for a disguise. Exploring identity, the mythology of bushranging and the invisible history of women, these images pay homage to the solitary, camouflaged figure of Jessie Hickman.

Smother is a contemporary reinterpretation of the life of the much loved Lady Bushranger Jessie Hickman (1890-1936) who adopted many roles and disguises as a young, travelling circus performer and in later life as a bushranger in the Kandos/Rylstone region of NSW. Williams photographed Kandos locals in locations known to have been frequented by Hickman to reveal her elusive identities in a historical context, where women shift like phantoms through the archives with names and roles ever-changing. Much like the mysterious, hand printed final imagery that emerged from the film negatives in a traditional black and white darkroom. The word ‘smother’ is circus jargon for a disguise. Exploring identity, the mythology of bushranging and the invisible history of women, these images pay homage to the solitary, camouflaged figure of Jessie Hickman.

Exhibitions and Events

2022 Julie Williams & Sally McInerney in conversation with Fiona MacDonald: The Life and Times of Jessie Hickman. Kandos Museum, Kandos NSW

2022 Finalist Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize Muswellbrook Regional Art Centre, NSW

2022 Smother Cementa22 Arts Festival, Kandos Museum, Kandos NSW

2022 Julie Williams & Sally McInerney in conversation with Fiona MacDonald: The Life and Times of Jessie Hickman. Kandos Museum, Kandos NSW

2022 Finalist Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize Muswellbrook Regional Art Centre, NSW

2022 Smother Cementa22 Arts Festival, Kandos Museum, Kandos NSW

Awards

2022 Honourable Mention for the image Moth, Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize Muswellbrook Regional Art Centre, NSW

2022 Honourable Mention for the image Moth, Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize Muswellbrook Regional Art Centre, NSW

Publications

2022 H.R. Hyatt-Johnson. Cementa22, Review, Artist Profile, Issue 60, pp 158-160

2022 Inside Imaging: Sammy Hawker wins Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize

2022 Australian Photography: 30 Finalists announced in 2022 Mullins Photography Prize

2021 Arts OutWest Micro Grant Stories: Julie Williams' Smother project

2021 Arts OutWest Arts Restart Micro Grant

2022 H.R. Hyatt-Johnson. Cementa22, Review, Artist Profile, Issue 60, pp 158-160

2022 Inside Imaging: Sammy Hawker wins Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize

2022 Australian Photography: 30 Finalists announced in 2022 Mullins Photography Prize

2021 Arts OutWest Micro Grant Stories: Julie Williams' Smother project

2021 Arts OutWest Arts Restart Micro Grant

Essay

2022 McInerney, Sally. The Return of Jessie Hickman.

2022 McInerney, Sally. The Return of Jessie Hickman.

Her

Bridled

Smother

Ngama

Widden

Colonial Nester

The Other

Hers

Our Eyes

Fayre Martin

Float

Moth (Honourable Mention, 2022 Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize)

The Return of Jessie Hickman

essay by Sally McInerney

essay by Sally McInerney

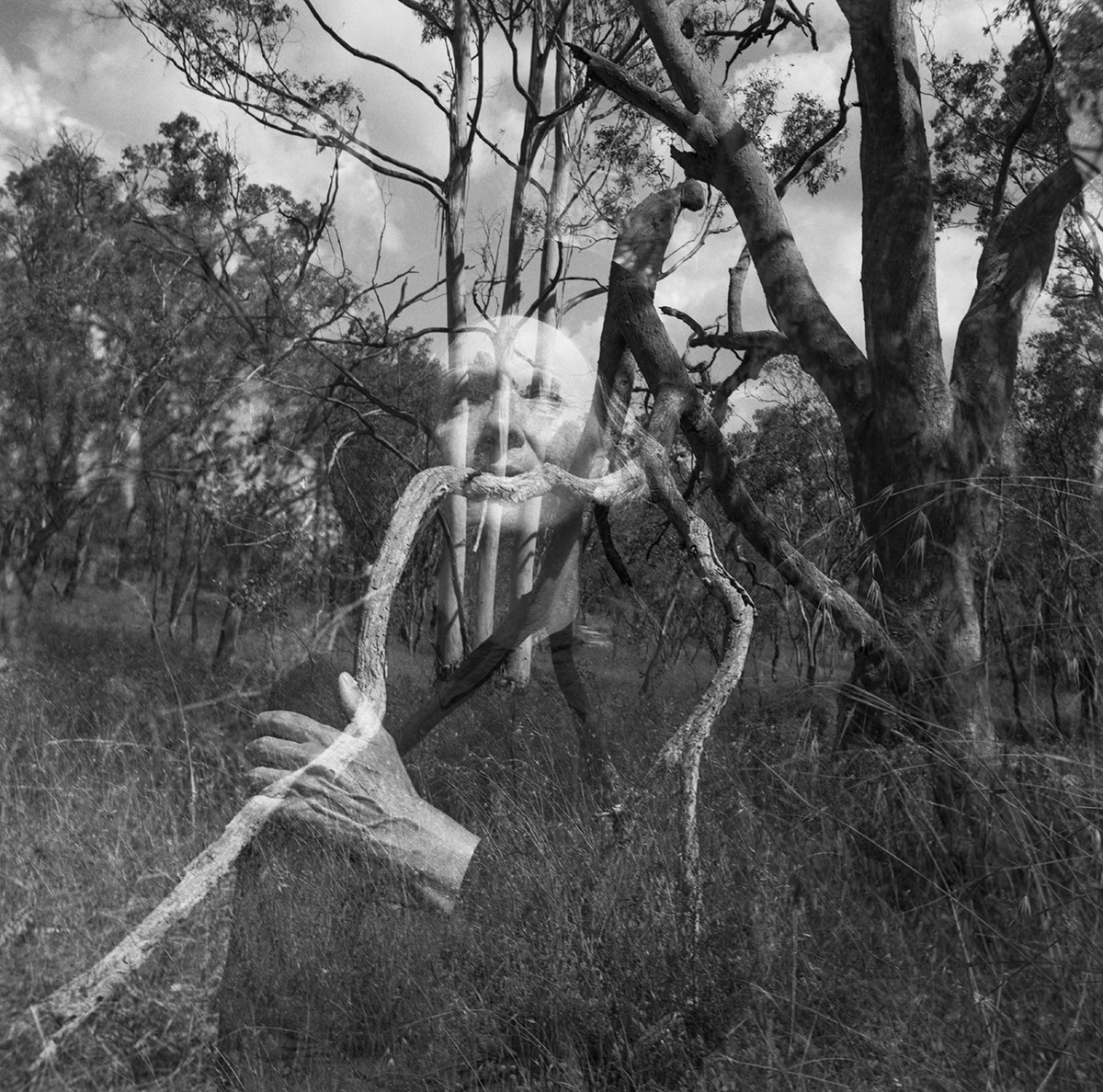

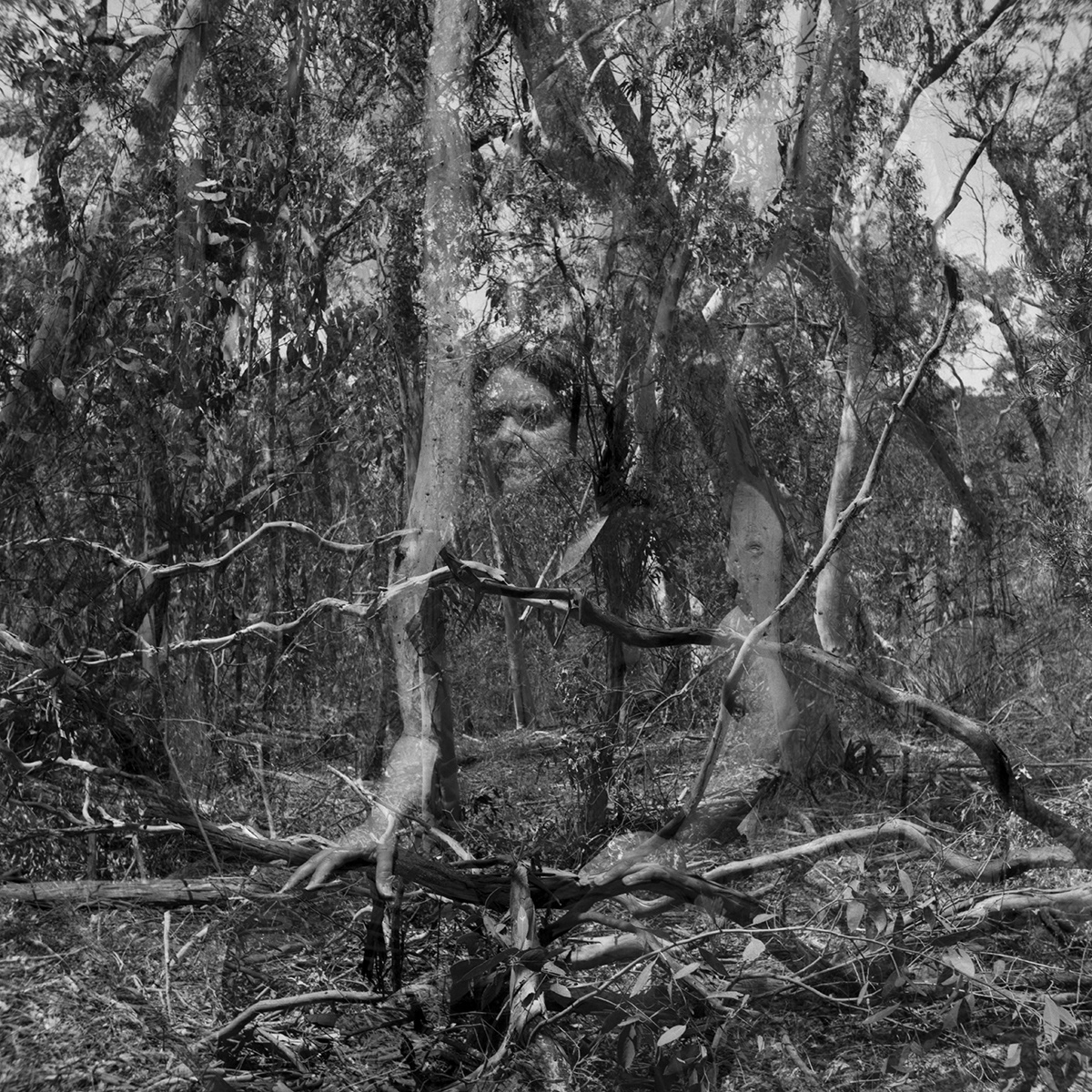

Julie Williams is an artist who inhabits the world of nature with all its light and darkness. She lives in the same kind of country as Jessie Hickman, a woman of many aliases, who is the subject of Williams’ new photographic series, Smother. These thirteen images were all made outdoors, in locations frequented by Hickman during her makeshift years as a young woman sometimes portrayed in folkloric hearsay as ‘the Lady Bushranger … elusive in pursuit’.

In bringing the shady figure of Jessie Hickman back to light, Williams adopts the name ‘Matilda Breheny’ as her own alias and alter ego. Like Hickman, she grew up with horses. As a nine-year-old equestrienne, riding on local stock routes, visiting the pit ponies at the nearby Muswellbrook colliery, she thought of herself as a centaur. She understands how a hardy young woman could live part-time, as Hickman did one hundred years ago, in an almost inaccessible cave on Nullo Mountain, secure in that eyrie with a long view of the valley, a good getaway horse and a blue enamel teapot patterned with flowers. She knows how the muted earth colours in eucalypt forest provide the best camouflage, while stillness and silence can make a living creature invisible.

Williams’ recent work, Monumental, was an elegiac record of the fire-devastated bushland near her home of twenty-five years in the Vale of Clwydd at Lithgow. Having fled the fire-front just in time to gather the three most important things — her cat, dog, and photographic archive — she came back days later to that blackened country and photographed it in pure colour with a smartphone, near ground level, breathing ash, getting dust in her eyes, charcoal on her clothes and limbs, the fallout of the traumatised land. For an earlier photographic project in Argentina, Deciphering the Unseen, she and fellow artist Ruth Thompson rode into the foothills of the Andes to make a series of double-exposed self-portraits. There is a sense of the women’s light freedom in a landscape of rocks and sun-bleached animal bones, with horses as allies standing by.

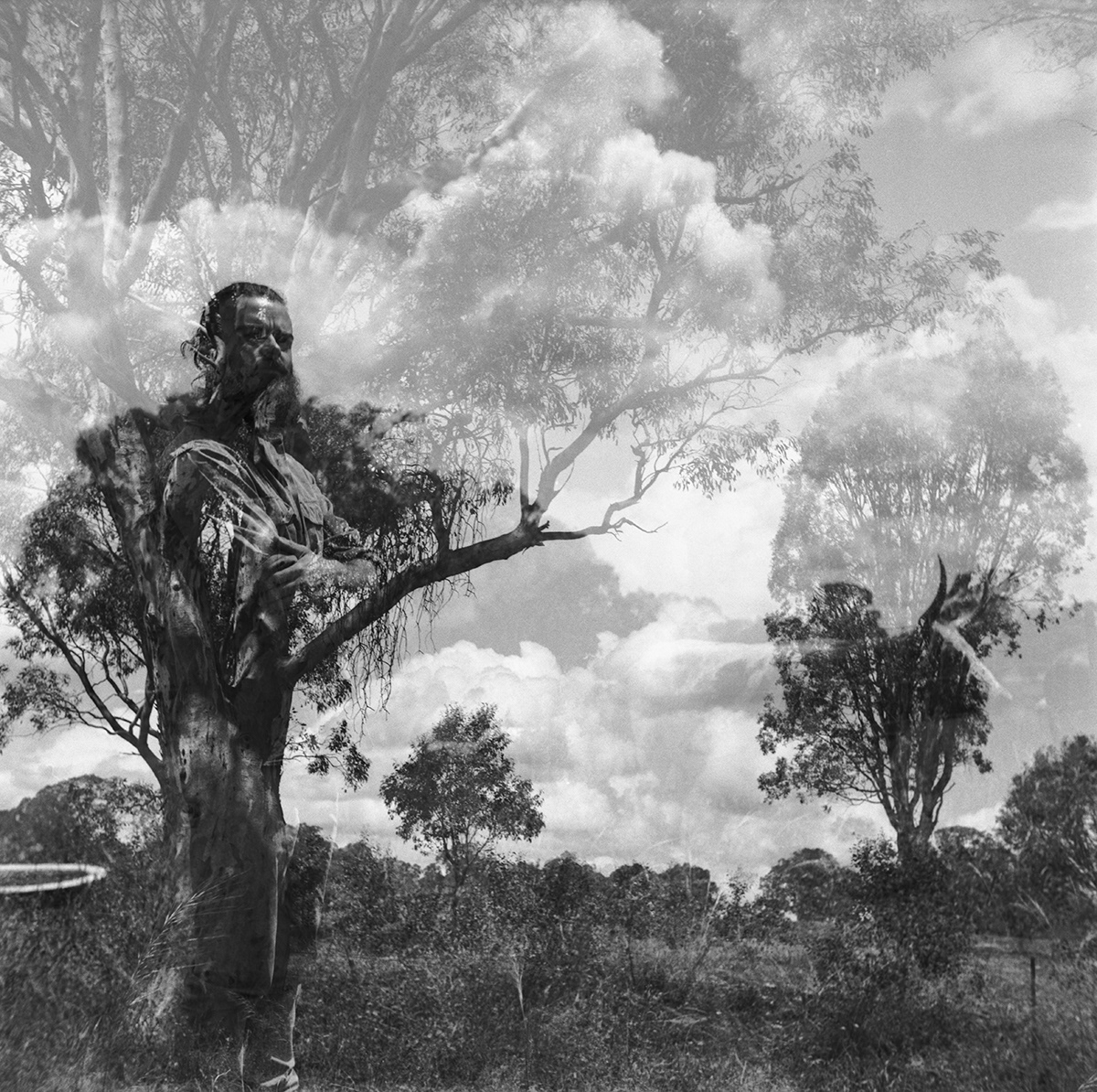

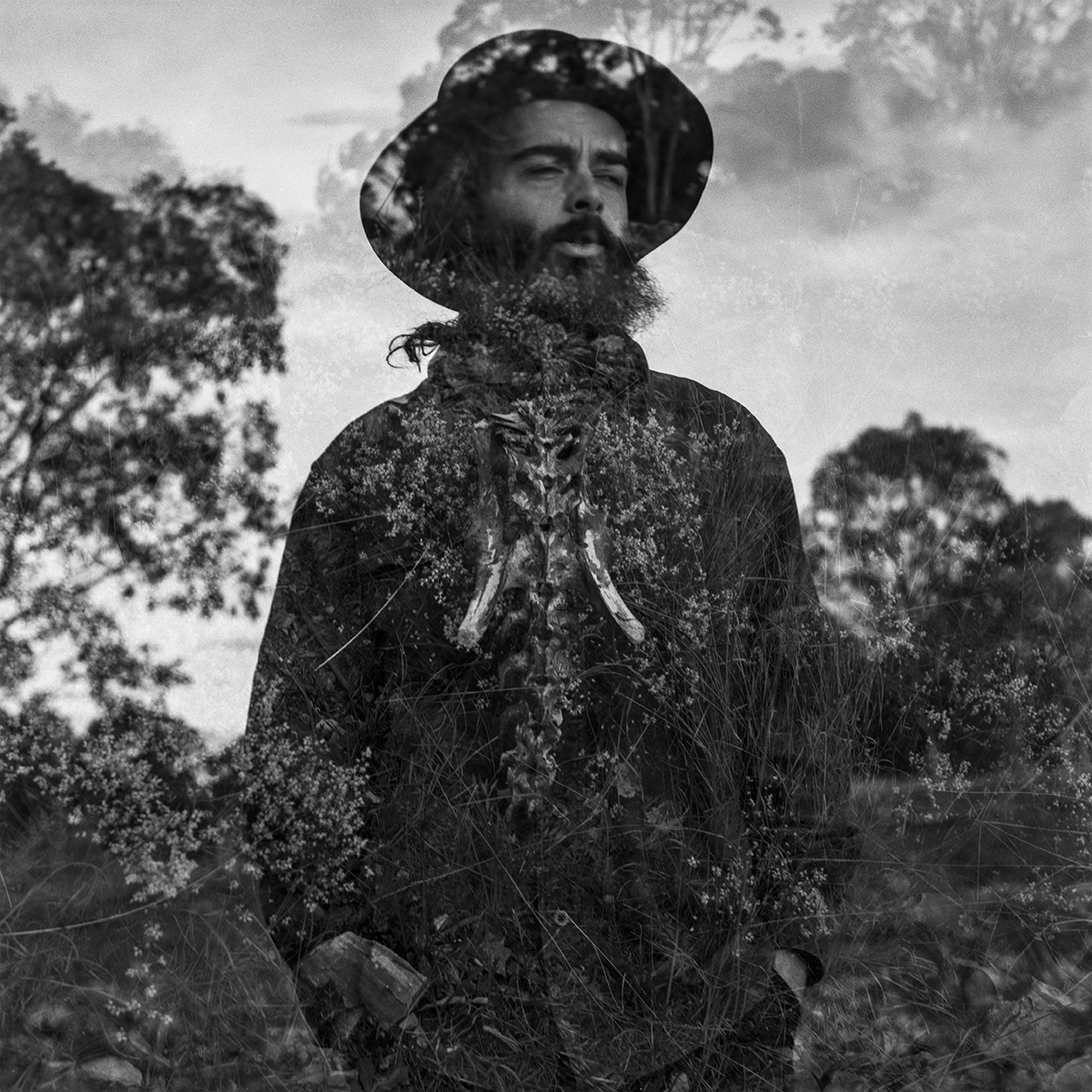

The Australian bush has challenges for an artist working outdoors. The ground is uneven; breezes, clouds and animals may intervene. The dry sclerophyll forest of the Blue Mountains and beyond is difficult to encompass with the naked eye. It’s like a full orchestra playing in visual form, with dominant shapes and intricate detail near and far, the overstorey and the understorey flowing through endless tonal galleries. For Smother, Williams returns to the medium of black-and-white film double-exposed within the camera, a practice at which she is wondrously skilled. As she says, it can take you another step further into the bush.

In each of these extraordinary photographs, two moments, separately captured, coalesce to form a parallel world which floats in a third dimension of time. A pale blurred face, like a transient shape in cloud, gazes from a rocky outcrop that resembles wings. This is Olinda, named for the place where, it’s said, Jessie was given a cup of tea as she sat, apprehended for once, in a police cart beside a farm house. A girl looks out from a vantage point on Nullo Mountain while subtle lines of water run across her body. A woman in a plain dark dress stands at the mouth of a cave with shards of light at her fingertips: it is her colonised cave, her nest.

In Fayre Martin a girl merges with a stand of spiky agaves planted by old land-clearing farmers long ago. Between the tame world and the wild, she looks towards us from the agave palisade, with the stoney ramparts of Capertee Valley behind her. An older woman is being absorbed into the forest. There are pockmarks on her arm, which has become a tree, and a long white branch reaches down over her disappearing self. Leaf patterns lie like veins on the skin of other women, and sometimes light catches their weathered hands at rest.

They are all manifestations of Jessie Hickman, also known as Jessie Hunt, Elizabeth McIntyre, Jessie McIntyre, Mrs Bell, Glen Murray, Jessie Glen Thomas, Mrs Hudson, Mrs Payne. Born at Burraga in 1890, Jessie Hunt was nearly nine years old and skilled at handling horses when her hard-pressed mother apprenticed her to a travelling circus, quite likely a family troupe specialising in clever equestrian performances.

By late 1901 she had joined the fledgling rough-riding show of Martini Breheney, whose harmonious name I used to hear as a child, spoken with respect by the old horsemen of my family. James Martin Breheney, already well known as the spellbinding circus gymnast Signore Martini, was branching out on a new venture. His wife, Julia Kelson (a serio-comic singer and dancer whose stage name was Jessie Devine) and her sister, Mena Val (a skilful trick cyclist and whip cracker) were his founding crew. They took young Jessie under their wing and set off from Sydney as a small side-show with a wagonette and a tent. Their precarious luck turned at Lithgow when they acquired a high-spirited horse named Misty, soon to be wonderfully notorious as Dargin’s Grey.

Martini, Julia, Mena Val and Jessie formed a loyal nomadic clan, together with the legendary half-Aboriginal horseman Billy Waite. They toured northward as far as Thursday Island, picking up ‘outlaw’ horses and fine riders all the way, and by the time they got back to Sydney, their buck-jumping show was famous throughout Australia.

Jessie was sixteen when Martini was killed, aged thirty-nine, in a freak accident at Armidale while getting a cartload of sawdust for safe landings in the ring. A broken column for a life cut short still marks his ornate grave at Waverley. The show resumed its scheduled tour three weeks later with a heart-broken crew, and his widow thrown into the role of manager and ring-mistress.

A good-looking figure, bearded and rangey, appears in Smother, a dark rider who looks into horses’ eyes. There is no subterfuge about him. In Widden he is an arboreal centaur, scanning Wiradjuri land from the top of an old eucalypt tree. He is Moth, the wayfaring storyteller and memory-keeper, who travels the country on foot, alone. He is a riddle who knows the answers. Clouds float on the brim of his hat, and delicate kangaroo bones lie on his chest like an X-ray.

Martini’s Buck-Jumping Show survived until 1911 when Julia, worn out and ill, sold the horses to a syndicate which shipped them to England for displays of Wild Australian horsemanship. Mena Val, Billy Waite and some of the other performers sailed with the horses. The remaining horse-handlers, acrobats, trick cyclists, gymnasts and whip-crackers were adrift, looking elsewhere for work.

Circus fortunes faded as World War One began gathering its human fodder from city and countryside. Jessie endured a period of poverty and crime in the Sydney slums. Fixed in place, expected to care for inanimate things, she would not settle for domestic life. She had not lived in a house since she was eight years old. Early in 1913 she had a baby with Ben Hickman, a dashing sailor from Oxfordshire, and gave the infant to a trusted childless friend. Very soon she came to public view in newspaper and police reports as Jessie McIntyre, an accomplished equestrienne, lately of Martini’s buckjumping show … Wild and lonely life … Young circus rider … Wild, roving, and dangerous life … A Girl on her Trial … She had lost her parents when a child and had been living with relatives … The girl sat down with a smile on her face … She lived a roving life … Jessie and the Gelding … Girl circus rider sent to reformatory … Jessie and the Jersey Cow … Jessie, John, and the Battle-Axe … Elizabeth Hickman, wanted on warrant.

Magistrates were inclined to go easy on her, at first. It was alleged that she had stolen ducks and fowls, a mare, a pony, a black cow, a Jersey cow, a horse rug, a whip, a carriage lamp, a sulky with harness, and had doctored the brand on somebody else’s chestnut gelding. For a while she lived in a hut on the edge of the bush at Oakdale with a male accomplice, until they were both sent to gaol for theft and larceny. Jessie was the mastermind and got the longer sentence.

Eventually Ben Hickman, home from the war, informed the Divorce Court that his wife had told him she ‘would sooner live under a sheet of bark in the country than live in the city’ where he was employed, adding that she had always been very fond of animals, especially horses and cows. Divorce was granted on the grounds of Jessie’s desertion.

She took to the wild country of Nullo Mountain where she had a hut of her own near a place named Stoney Pinch, with some sympathetic farmer neighbours and an escape route to her place of greater safety, the cave. She remained adept at handling, or stealing, horses and cattle. Despite spells in gaol it seems that she was unintimidated, sometimes even amused, by her court appearances and skirmishes with the police. She was, after all, a well-practised performer.

Eventually she quietened down, died young and faded into folklore. Yet she was real, and here she is in several guises, a wild spirit looking us in the eye.

© 2022 Sally McInerney

Sources and further reading:

National Library of Australia and Trove Partners. https://trove.nla.gov.au/

National Library of New Zealand, Papers Past. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/

Geoff Greaves, The Circus Comes to Town. Reed, Sydney, 1980.

Norma Brophy with Wendy Stuart, Don’t Call us Carnies. Affirm Press, Melbourne, 2022.

Di Moore [Jessie Hickman’s grand-daughter], Out of the Mists. Balboa Press, Bloomington, 2014.

Katherine Susannah Pritchard, Haxby’s Circus. Cape, London, 1930.

Mark St. Leon, Circus. Melbourne Books, Melbourne, 2011.

The Lady Bushranger, Pat Studdy-Clift. Hesperian Press, Carlisle, 1996.

National Library of Australia and Trove Partners. https://trove.nla.gov.au/

National Library of New Zealand, Papers Past. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/

Geoff Greaves, The Circus Comes to Town. Reed, Sydney, 1980.

Norma Brophy with Wendy Stuart, Don’t Call us Carnies. Affirm Press, Melbourne, 2022.

Di Moore [Jessie Hickman’s grand-daughter], Out of the Mists. Balboa Press, Bloomington, 2014.

Katherine Susannah Pritchard, Haxby’s Circus. Cape, London, 1930.

Mark St. Leon, Circus. Melbourne Books, Melbourne, 2011.

The Lady Bushranger, Pat Studdy-Clift. Hesperian Press, Carlisle, 1996.

Sally McInerney, writer and photographer, grew up on a small farm near Cowra. Her father’s family have lived in the district since 1863, hence from childhood she heard stories of local bushrangers Ben Hall and Johnny Vane, with whom some of the family were acquainted, and of the fine horsemen Martini Breheney and Rhody Sheedy (who became a family friend, sometimes known as the 'last of the bushrangers’). Sally maintains strong ties with the Central West. Her artist’s book, Family Fragments, about interwoven lives in city and country, has been exhibited at Bathurst Regional Art Gallery, Cowra Regional Gallery and the State Library of New South Wales. Cowra Regional Gallery holds work by her mother Olive Cotton and by Sally herself.